I wrote this a while ago. I can’t remember what it was for?? Anyway, I’m still catching up on life now the kids are back at school, so I thought I would share it here.

I hope you’re all well. It’s absolutely peeing it down here so I’m very glad we did a last minute dash down to the sea for a swim on Wednesday.

WARNING: This newsletter contains references to death, gallows humour, and regular mention of a revolting family habit (that is: turning every little event into an anecdote and making people listen to it like we’re bloody Ronnie Corbett or something.)

At 6.30am I got a call.

“Katie, Dad’s dead.”

It was the call I’d been dreading for my entire adult life. My father had been ‘dying’ for almost as long as I could remember. He’d had his first heart attack when he was 40, then another one, and another. I’m not even sure how many in the end. They punctuated my childhood and kept us all on a knife edge.

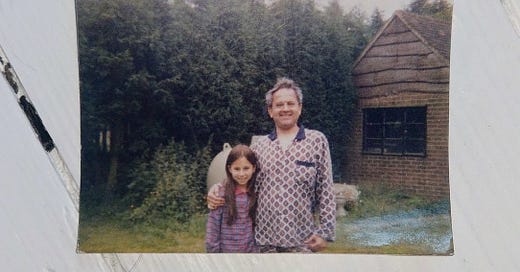

His life had felt precarious for so long I’d almost forgotten what it had been like before, back when he’d been fun and full of energy and silly walks. When I knew him best, he walked slowly and sensibly through life, occasionally stopping to squirt angina spray under his tongue1, always telling people how ill he felt if anyone asked. (No silent stoic suffering for him, thanks very much).2

The call came from my sister, Caroline. I always knew it would come from her (and she had got in trouble in the past for leaving “ring me back urgently” messages that turned out to be about which shoes she should get, or whatever). The call had to come from her because there is a family grapevine and it works a specific way. Here’s how (pay attention, this gets complicated). There are six of us: five girls, one boy. Yes, really. I am Number Six. Liz, for reasons too complicated to go into here, has always been Head Sister, despite her second ranking, which is why our mother rang her first. Caroline (Number Five) had been called by Liz (Number Two). My job was to call Number Four while Caroline rang our brother (Number Three) and Liz rang the eldest (Number One).3 Got that?

So I did my bit. I woke up Number Four and told her the bad news.

“Dad’s dead,” I said. I don’t remember what she said back, but it wasn’t a long call.

At one point, when I was still a small child, dad had heart bypass operation. For a few glorious weeks he was back to his old self. But then his new arteries clogged up and he was back to stepping slowly, trudging through every day as carefully as he could. Running a failing business didn’t help his stress levels. Eventually, after years of struggle and angina attacks, he had to give it up, and – much to his embarrassment – register as disabled. He felt like a failure, and he had many empty days to spend dwelling on that failure. I think about that a lot now I’m older.

He spent his time avoiding stress, eating saltlessly, fatlessly, joylessly; reading books, listening to the wireless and – the highlight – wrapping up in millions of layers to take the dogs for a long, slow walk. He was from Pakistan so he was always cold. But the tablets thinned his blood and made him even colder. After he died my mother donated all his jumpers to charity and I regret to this day not making a huge blanket out of them. It would have been nice to cuddle up with on the sofa, like we had done as children, him watching the news with a child under each arm.

After the mass Calling Of the Disparate Siblings, Alex and I sat around feeling dazed. But, after just a few minutes, the phone rang again. It was Caroline (Number Five). This time she was wheezing with hysterical laughter.

“He’s not dead!! He’s not dead!” she said again, gasping for air.

“What?!” I said.

“The nurse got the wrong bloke. It was some poor fella in the bed next to him. He’s still alive! Apparently the nurse is devastated.”

The nurse’s feelings were considered many times through the next few days. My mother made a point of mentioning them regularly.

“She’s ever so upset,” she’d say. “She’s terrified we’re going to get her in trouble. We mustn’t say anything.”

At all costs, the nurse’s feelings must be protected.

Caroline was still chuckling heartily and I joined her, incredulous at first and then delighted.

Only dad could turn dying into an anecdote.

But Caroline had sobered up by now. “He’s still dying though, so we’ll have to get up there.”

That sobered me up too. “I suppose we’d better ring the others.”

Number Four’s reaction when I called was much the same as mine. She cackled in delight at the cock up. We have developed a dark gallows humour about death, we lived under its shadow for so long that we are callused. Despite our many differences, it’s one of the things we have in common. And we love a good story.

Boy, did dad love to spin a yarn. On one of his good days, he would tell us tall tales from his time in the navy. How he’d won a boxing competition despite being 5’5 and skinny (he talked his opponent into going easy on him). How he’d driven the wrong way up a one-way street without a driving licence, but then played it so innocent with the officer who stopped him that he got let off without a ticket (or arrest for driving without a licence). How he’d flown over the Eiffel Tower in a plane, pulled his trousers down and scratched his bum on the top as he passed (my brother famously believed this one for years).

Often he would tell us about his strange childhood filled with stark horrors and loneliness. How he rode a little pony in Lahore that used to plod sluggishly all the way round one half of the hill and then go like the clappers for the second half in its eagerness to get home. How he was sent to boarding school at five years old for six months of the year and the nuns tied his left hand behind his back and hit him with a stick any time he used it.

He’d been having more and more good days in the years before his death. The doctors installed a TENS machine inside his body which stopped the pain in his chest. He switched it on and off with a magnetic remote control held to his stomach. (It was unclear to me if he really couldn’t go into WHSmith to buy books for fear of setting off the security alarm, or if that was a joke. Even he didn’t seem sure after a while.)

Now he could walk quickly. No more slow-trudging through life. The dogs didn’t know what had hit them. He lost stones in weight and he started to laugh again. On one of those days he’d have enjoyed the anecdote about him dying and then not dying and then dying again.

Caroline and I travelled up in the car together. I remember it as a funny trip, but that might be because I wrote a script about this episode of my life, and this is a funny scene4. Caroline had recently had her first baby and was still recovering from a C-Section. I look back (now that I’ve had kids myself) and cannot fathom how she handled it so well. We arrived at his deathbed, where my other siblings were gathering.

Or, more accurately, where Numbers Two, Three, Five and Six were gathering. One and Four preferred not to attend since One didn’t like hospitals (unlike the rest of us who love to hang out in these houses of the sick whenever the chance arrives, drinking bad tea, inhaling the weird smells, seeing very ill people facing their mortality, and paying obscene parking fees), while Four felt it would upset her too much (while the rest of us were all super buoyant and cheerful about the whole situation).

This anecdote about my dad being dead and then not being dead doesn’t end here, but it’s hard to know where it ends.

Does it end with my fury and sorrow at discovering he was dying not of heart disease as expected, but of C-Difficile, a super-bug he had picked up the last time he was at this filthy hospital?5

Perhaps the ending comes when my brother told him he was going to shave off the Abraham Lincoln beard my dad now sported (having grown bored of all that time he spent in the bathroom), prompting my father’s face to wrinkle in humorous concern so that we suddenly realised he could hear us and was still our father inside somewhere.

Or does it end with sister Number Two asking him – now he was almost conscious – if we should turn the life support off? Or, when he screwed up his face and nodded, eyes still shut? Perhaps it was when Number Two, overwhelmed with bearing all the responsibility, told me to ask him again so we were absolutely sure he’d said yes.

Was it when he once again nodded his head grimly, awake enough to know he didn’t want to be awake any more?

Maybe the big finale comes when I stood with my brother and looked at my father’s corpse, his mouth wide open, the nurses unable to get it closed.

“He’s giving his last orders,” said my brother and we both laughed.

One nice ending is when we all went to Pizza Hut and had a really awful meal and the next day the Pizza Hut burned down.

Another is when we discussed how he’d wanted his ashes scattered at the woodland I own and we considered building a composting toilet in his memory and dumping the ashes down the hole – since he spent so much of his life in the lavatory. And then we all laughed for ages.

Perhaps it was when we gathered for the funeral and Number Four finally made an appearance and said to me, “In many ways by not being there it was like I was MORE there, you know?” and I managed not to yell, “But you weren’t there!”

Maybe it was when my phone rang in the middle of his funeral – right when I was reading the eulogy, after I’d told the anecdote about dad scratching his bum on the top of the Eiffel Tower. Or when I cried during a disastrous wedding dress fitting and said, “We were only getting married so dad could come before he died and then he went and died,” and the dressmaker went paler than the dress.

There’s never any neat ending to an anecdote about a loved one dying, no punchline (beyond the finalist one of all). The grief stretches on and on. And in the end, all you really have left are the stories you tell…

Dear me, that’s a schmaltzy line isn’t it? Yuck. Too schmaltzy for my family. No thank you.

Here’s a better, truer one (but not as neat, damn it). In the end, what really happens is you start to worry if you’re remembering the stories right. Did he also convince my brother he collected his farts in jars? I can’t remember if that was him. Was the priest at his evil convent school in Lahore really called Father Kissalice?6 Did the Pizza Hut really burn down the next day?7

When you’re a family that prizes anecdotes told over and over (and over and over), how eroded do the memories get? The year my dad died was one of the few years I didn’t keep a diary. It was also one of my most stressful years – one I spent a long time trying not to think about. Writing a fictionalised version of his death into a three-act drama didn’t help. Trying to pin down the truth from the tales is harder the older I get: me, known in my family as the one who remembers, scrabbling to recall his exact words; trying to remember what happened the day he died.

So, yeah, anyway. There is no neat way to finish this. He did die in the end, and it was a real bummer. But I guess I should give a shout out to the nurse who cocked up that initial phone call – there’s a chance we wouldn’t have been there when he died without her. And it gave us something to laugh about.

PS. I once saw a tweet (or an article?) about someone who absolutely despises the notion of having or telling anecdotes (along with those who do have and tell them) and it had genuinely never occurred to me that being able to spin a yarn wasn’t a Good Thing. I guess that person doesn’t want to hear my very long story about a cleaner we had who may or may not have tried to poison someone (complete with my very authentic and possibly problematic impression). Or the time we lost Glastonbury Festival and ended up in a field full of horses. Or the day I thought I was going to die in the Thames with a ten year old. Or that time I didn’t realise I was meeting the Queen. As my dad would say, “Well, sod you then.”

I tried it once. I genuinely have no idea why. I was normally a sensible teen – I didn’t do (most) of the drugs my generation did. I found out later it was amyl nitrate - poppers. Or maybe I already knew and that’s why I tried it? Anyway, anything could have happened, but nothing did, so that’s the end of that story.

I think he remained amazed and scandalised that his illness had stolen his old life from him and I can’t say I blame him. I think I’d be the same. I was bad enough when I got a neck injury and had to quit my yoga cult.

The politics of this is a whole other saga

Well, I think it’s funny, anyway. My agent was getting quite promising responses to the script but then the pandemic hit and no one wanted hospital dramedies so I shelved it.

Historically much in the news for its lamentable record.

Ancestry.co.uk leads me to suspect it must have been Kissalis, but I still couldn’t find a priest in Lahore with that name.

No, I checked. It was a month later.

Love this piece. I’m glad that you didn’t find out your father had died via a phone call that said, “Dad’s dead.” 😳🙈 It’s a beautifully written tribute — and funny. I lost my Father this year and it just sucks! Sending love and best wishes. 🫶🏻

Love this. My mum died two years ago and sharing anecdotes is where I am at now. Anyone who spoke to her came away discovering they'd been volunteered for something and they had no idea how. A couple of years before her death I discovered that she quite enjoyed mispronouncing all the words that had had us in stitches over the years. Such as broccula, which as a family we turned into 'broccula the vegetable of the night.